Classicism, Realism, Avant Garde: Italian Painting in Between the Wars

Texts on some works

Aldo Bonadei - Natureza-morta,1950 >topo

With a classical education at the Academy of Fine Arts in Florence , Aldo Bonadei approached modern painters and theories when he went back to São Paulo . In 1935, the artist installed his studio at Santa Helena Building with Francisco Rebolo Gonsales, Mário Zanini, Humberto Rosa, Fúlvio Pennacchi and, after a while, Clóvis Graciano and Manoel Martins. He had his first individual exhibition in 1944 at Brasiliense Bookshop, took part in the III Bienal de São Paulo (1953) and was one of the Brazilians at the XXXI Venice Biennale (1952).

On the one hand, Santa Helena Group allowed Bonadei to review his aesthetics and, on the other, the experience of producing being a part of a collective, which had as main proposal the domain of craft.

Bonadei didn't abandon figuration, but that started to be designed through a personal interpretation, turned into geometrized shape. In order to understand that movement, the painter's still lifes are fundamental. They are one of the main motifs of his production, and play the role of reflection about the practice of painting itself. The author has still lifes that go from the most classic to the most abstract ones.

There are, in this still life, the geometrized shapes, simplified and determined by the lines, and reinforced by the color, almost functionally, but maintaining the motive of still life.

Maria Lívia Góes

***

Felice Casorati - Nu Inacabado,1943 >topo

Born in Novara , Felice Casorati achieves recognition as a painter with his arrival in Turin in 1918. In 1923, Casorati opens a painting school on his studio, at a time when rethinks metaphysical painting, Cézanne's legacy and is interested in the Italian Quattrocento . The formal accuracy that he achieves in these years makes him one of the representatives of the so-called "Return to Order" in Europe . This period is marked by his special room at the Venice Biennale in 1924, and his participation in the I Mostra del Novecento Italiano , in Milan in 1926. In 1928, his painting goes through a change of style, beginning to be characterized, according to some specialists, by a further chromatic research and a more fluid drawing. The 1930s and 1940s are marked by the celebration of his work: at the I Quadriennale di Roma in 1931, he is given a special room and receives the third place award in painting; and in 1941, he is invited to be a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Turin , of which he became director in 1952.

Unfinished Nude seems to synthesize a series of elements of Casorati's painting, especially his experience after the I Mostra del Novecento Italiano and the affirmation of his autonomous style, particularly on the work of application of layers of colors and their transparency. On a lecture given at the University of Pisa, in May 1943, Casorati sumirizes his work, emphsizing the importance of his chromatic research, asserting himself as a painter who built his own line of research of color: one that seeks realism. In his painting compositions there is a large number of nudes, of which is even greater the number of studies. In the latter, Casorati states that one can recognize the most vital elements of his painting. Casorati spent much of his life drawing nude female figures in interiors, which since perhaps his Platonic Conversation (1925, oil on canvas), exhibited at the I Mostra del Novecento Italiano , are for him essentially an issue of painting and form, of research of his style, and run parallel to his production of still lifes, as in Still Life with Lemons , also present at the exhibition. The painting alludes, therefore, to the exercise of painting, and later unfolds in countless versions of compositions of nudes in his studio, which he revisits until the end of his life.

A peculiar element of our Unfinished Nude is that it carries on its back a painting, a work by Daphne Maugham Casorati (1897-1982), the painter's wife. Of British nationality, and niece of the great writer William Somerset Maugham, Daphne was a student of Casorati's painting school from 1926 on, becoming his wife in 1930. The discovery of the painting of her future husband was, for her, marked by a great transformation in her style. Trained in the Parisian artistic milieu of the 1910's, Daphne had experienced the visual language of Cubism, but experts tend to identify on her painting a huge affinity with Impressionist techniques. The study, being conducted in collaboration with the group of nuclear physics from the Institute of Physics at USP, could elucidate the differences we see between the painting style of Casorati and his wife, Daphne: details taken especially in the elaboration of physiognomy of the two figures represented, reveal how the two artists effectively proceeded very differently.

What probably would have taken Casorati to reuse Daphne's canvas is probably due to the fire that consumed the artist's studio in 1943, when he was busy with an individual exhibition of his recent work at the Galleria Il Cavallino, then owned by famous collector Carlo Cardazzo, in Venice . He presented then a total of 22 works, ten drawings and 12 paintings, among which he exhibited nine nude compositions. This is also the moment perhaps that Cardazzo himself acquired a female nude study from the artist.

Ana Gonçalves Magalhães

***

Achille Funi - A Adivinha,1924 >topo

Funi, alongside Sironi, was the artist that for the critic Margherita Sarfatti, starred Italian modern painting defended in her notion of Novecento Italiano , which she thought as the most legitimate manifestation of the new socio-political order established in her country from 1922. Therefore, in her exile in Argentina and on the guidance for the Matarazzo couple's acquisitions, the presence of The Fortune-teller in the list of works purchased seems to witness the meaning of this moment in the history of Italian modern art.

It is possible to put it in context of the production of Funi's so-called Magic Realism, between 1920 and 1924, also the moment of establishment of the Novecento group, around Sarfatti. Reviews of his work from this period often mark its relations with Ferrarese Renaissance, above all the influence of Flemish school on the Ferrara 's Quattrocento . Funi's composition for The Fortune-teller works with some canonical elements of such references: the figure positioned at ¾, its pyramidal structure, the position of the arms, the relation between figure and background, and the modelling of the figure from the construction zones of light and shadow. It also retrieves certain aspects of Renaissance art, such oil on wood and an important conceptual reference: the painting is executed in golden ratio. Regarding the pictorial culture of Ferrara 's Quattrocento , experts always remind the relation of Funi with the work of Cosmè Tura.

The painting seems to respond to the controversy with the group of metaphysical painters few years before. Architectural elements in the background of the composition actually allude to porches painted by De Chirico in his versions of the so-called Piazze d'Italia , of the years 1910-14. After x-ray analysis recently performed on the work, we see in fact a background later eliminated, which refers to the atmosphere of the views of De Chirico, while it refers to images of the Renaissance ideal city. At the same time, The Fortune-teller presents itself as an exercise on the reinterpretation of Renaissance's iconography, using the notion of synthesis, previously proposed by Margherita Sarfatti, which for Funi would not signify the imitation of Renaissance's masters, but the reference to the architectural traits of the composition, the pursuit of style, and the formal solid construction.

In at least two other works of the same period the artist articulates female figures from a purple drapery. This is the case of Head of Women (Figure, Female Figure or The Sister ), 1922 (private collection, Monza , formerly in the collection of Sarfatti). The solemn simple, concise and constructed character of these figures expresses the elements that, for Sarfatti, would be the foundation of a modern Italian painting, promoting the synthesis between avant-garde experiences and traditional Italian art.

Ana Gonçalves Magalhães

***

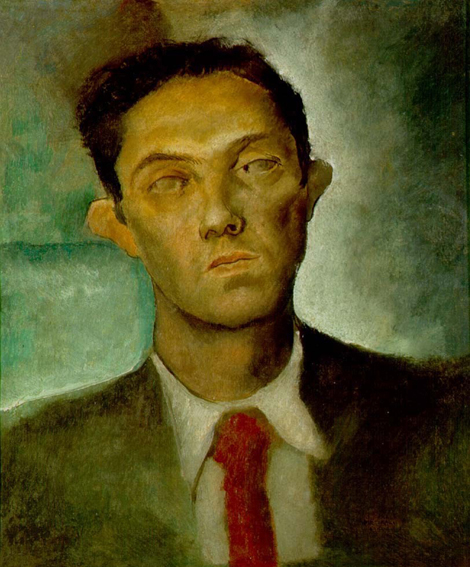

Alberto da Veiga Guignard - Autorretrato,1931 >topo

.jpg)

Of European training shared with most modern Brazilian artists, Guignard returns to Brazil in 1929, having already participated of the XVI Venice Biennale (1928), but with a background different from most artists in the context of the second Modernism. His reference that carries a lot of the surrealism is present in almost all the subject-matters explored by the artist, from still lifes, not so present in his work, to landscapes and even families, more representative.

The portrait, also one of the predominant genres in his production, is the genre in which, beside Portinari, he stands out. That might be what makes Mário de Andrade recognizes him as the one of the revelations of the Salon of 1931, but simultaneously not granting him the same central role of Portinari and Segall, who explored more nationalistic issues.

What is remarkble in his portraits is the character of the portrayed person, being the portrayers often known by the painter. The self-portraits, as this one of 1931, make a total of 20, rendered with the same acuity to expose himself as to the pursuit of revealing when the other is portrayed, which approaches him to Rembrandt, both in the intention of honesty, and as a possible financial difficulty that prevents him from hiring models. The honesty is explicit both on the aging revealed in the paintings, as in his birth defect, cleft lip, almost always present, and that has deeply marked the personality of the painter.

Guignard has produced apart from the São Paulo group, having worked on Rio de Janeiro since his return from Europe until being invited, in 1944, to teach at the newly founded Institute of Fine Arts of Belo Horizonte, where he left a legacy of students such as Amilcar de Castro, Farnese de Andrade, Franz Weissmann, among others.

The formal content of Self-portrait of 1931, however, is reflected in his production and approaches him to the São Paulo 's artists of Santa Helena Group. In it, we find the expression of domain of the craft, which refers to Tozzi and Campigli, with an almost rough stroke of fine and precise lines, and the return to a realistic language, even if against a quasi-metaphysical background.

This metaphysical tone is marked by synthetic elements: the sea and the column with an aspect which refers to the Mediterranean , and in its turn, approaches the work also to Tozzi, and even more to De Chirico ( Horses By the Sea ) and Carrà ( After Twilight , 1927). Once again the background, of metaphysical character, but added to the painting's snippet itself, a bust, classical portrait posture, finally connecting the work of Guignard to Funi's Fortune-teller .

Maria Lívia Góes

***

Mario Mafai - Natureza-morta,1946 >topo

.jpg)

The subject-matters explored in Mafai´s work are portraits, the series that depicted the demolition brought about by Mussolini to Rome´s road works, and still lifes with flowers.

The interest in still life certainly stems from the exploratory possibilities of the genre for the exposure of the language; not by chance, it is one of the main genres developed by Giorgio Morandi, famous still life painter with glass bottle, figuration through which he develops metaphysical painting, whose placid composition aimed at representing universal themes (more than themes, “states of mind”), oblivious to the history of facts and men. Thus, De Chirico also preached the ritorno al mestiere [return to craft], that is, the valorization of the painted medium (canvas – ink – brush) typical of the painter´s craft, and worthy of the artistic tradition by excellence, in opposition to avant-garde experimentations of the new and unheard of media and techniques (collage, photomontage, etc).

Mafai refers to De Chirico and Morandi by acting in a similar way, electing still life with flowers to his own aesthetic research, with series that are pervasive throughout his entire career since the 1930s, evolving to expressionist traces in the 1940s, achieving the last abstraction experimentations in the 1950s.

It can be clearly noticed, all throughout his career, that the first compositions are developed vertically, essentially displaying dried flowers; but the essence of the discourse, that is built along the years, is the melancholy of the flowers as observation of death, that is, life that fades away. Mafai is painting a scene, or the representation of an instant that freezes, and is mainly long due to the passage of the flowers during the years, to the time it takes them to dry. As Argan points out, it is a lethargy state, almost death, or the long discouragement from the moment of the cut, which takes their life away (but not completely) up to the final dryness, where their mortal remains lie, its vegetable carcass already lifeless; yet, the state they are submitted to is not that of agony, but melancholy, or sound sleep. This mid-time, that is the melancholy of the flowers, is captured along the years by the use of color, figuration, outline, and composition – scene arrangement.

In this example, the flowers contain the still life melancholy, aided by the chosen palette which ranges from red to green, and do not bear the constantly depicted Mediterranean heat of Lazio.

Benjamim Saviani

***

Mario Mafai - Rapaz,c.1935 >topo

.jpg)

This painting was bought in Italy in 1946, and belonged to Carlo Cardazzo Collection and was exhibited in the II Quadriennale di Roma (1935), under the title Testa di Balilla , although in Brazil , it was inventoried as Young Man .

That is a juvenile profile of a brown- haired boi, who wears a balilla uniform, upon a greenish background, attentively staring straight ahead. This work has a recurring subject-matter in Mafai´s career. His juvenile portray series made in the first half of the 1930s are well-known, with tendencies to more reddish palettes, and later to colder palettes. Even so, the smoothness of the colors is always a constant.

The work is not dated by the author, but it is possible to identify many characteristics that if compared to his previous works in similar series, it gives us some clues about its position in Mafai´s oeuvre: in advance, we have the reference of the 1935 exhibition; besides that, we also have other famous works which have the puerile theme, which follows the same path of artistic research: the boy's portrait and the use of colors in pastel hues, varying between the red and the green palette, but with no defined background. These works are located at the beginning of the 1930s ( Ragazzo con palla e Ragazzo con palla (a terra) – 1932).

One of the most constant piece of information in such series is the composition, which refers to mural painting of the late-gothic and renaissance fresco, for instance; however, it is not about imitating the fresco, but its representation in canvas, that is, the painted texture .

Based on that, it is possible to identify Mafai´s research of the 1930s (that is going to be unfolded in multiple directions in the 1940s), within the context of the Scuola Romana : interest turns to the renaissance painting up to the baroque from Longhi and De Chirico, in a process followed by painters as Mafai. His painting, especially in this period, evokes Giotto´s mural painting and the painter's activity as a craftsman more than an artist, highlighted in this work of depicting the textures of the fresco, of the wall, of muratura ; working with tonalities more than with colors; not defining the painted surface. It is not mural painting, but the representation of mural painting in a canvas, in an evident and constant way.

Besides that, one can notice references to renaissance artists a little bit out of the cycles of the consecrated masters by the historiographyof the time: its composition refers to the painting profiles of the nobles, it is true, by Piero della Francesca, but also to the portraits by Gentile da Fabriano, or the portrait-medal by Pisanello, which evoke a Quattrocento Renaissance more “primitive”, less “consecrated” then.

It is interesting to look at Young Man and see many allusions to 14 th and 15 th centuries in Italy , and to specific painters of those days. The young man´s profile is clearly referring to this period, and possibly interprets an art historiography much further of the great Tuscan cycles, pointing to reinterpretations of the Italian north cycle, within Mafai that investigated Italian painting diligently and the range of originals/references, in an attitude also of protest or disagreement against the attempt of institutionalization of the Novecento Italiano , artistic movement sponsored by Fascism, which aimed to rehabilitate and conserve the memory of what was considered the great Italian art, comprised in the Quattrocento renaissance, among the great Tuscan masters. The polemic lies in the question: but, why should only Giotti, Piero della Francesca, Raffaello, these “authorized” be recalled? Why not also look to other cycles, other worthy masters, another Quattrocento ? Moreover – and that was Mafai's great quarrel with Novecento – why elect a more authorized art, one that is worthier of admiration, than other(s)?

Benjamim Saviani

***

Fulvio Pennacchi - Paisagem com Figuras,1941 >topo

Although Pennacchi's academic training happened in Italy, his homeland, the artist was closely aligned to his former master Antonio Pio Semeghini, stepping back from Futurism, Metaphysical Painting and from other movements who sought the recovery of an Italian visuality mainly after the Renaissance, as in Novecento, and was closer to the impressionist and post-impressionist legacies.

In Brazil, where he arrived in 1929 at the peak of the coffee crisis, and perhaps in search of the support of the Italian community who received the best art of the "Return to Order", Pennacchi sought to redeem classical ideals, which made him closer to the other artists of Santa Helena Group, with whom he exhibited at the 3º Salão de Maio (1939). His first individual exhibition was held at Galeria Itá (1944), and later on, at a more developed stage, he attended to the I Bienal de São Paulo (1951).

Unlike the rest of the group, though, his paintings, beyond the Italian form, also included subject-matters of his homeland, displayed in depictions of Italian scenes and the frequent religious themes. Scenes filled with “brazilianness”, as the village landscape of Landscape with Figures came to light only in the 1940s, precisely at the moment of greatest involvement with the Santa Helena Group, but did not remain for long, returning at the end of his life merged to the Italian themes.

Besides being a painter, Pennacchi was a renowned muralist and ceramist. In almost every household in which he lived in, he tried to build the environment in an artistic way, from the architecture to the frescoes and objects, as if he extruded his paintings and tried to reconstruct an Italian atmosphere, or, better put, an idealized Italian atmosphere with a certain Brazilian accent. A similar operation was conducted in Nossa Senhora da Paz, a church he decorated in São Paulo .

Maria Lívia Góes

***

Candido Portinari - Retrato de Paulo Rossi Osir,1935 >topo

Due to his training at the National School of Fine Arts (ENBA), Portinari has earned an academic insight that can be found in some of the portraits painted by the artist, especially early in his career. However, this is not the case of Portrait of Paulo Rossi Osir . Done when the painter had returned from a study trip to Europe, due to the Foreign Travel Award obtained in 1928, this work incorporates elements of modernism, thus revealing a more mature process of artistic production.

However, the modernism affiliated by Portinari does not mix up with the eagerness of the avant-garde, and is worth of what he was able to extract from the teachings at ENBA: the crafted aspect of painting and the recovery of some elements of the Renaissance tradition, allied to several currents that the painter would explore later in his works, remarkably cubism and expressionism.

With this style and using as a main theme the reality of the Brazilian worker, the artist became known as one of the greatest names of Brazilian Modernism, with commissioned works to the former Ministry of Education and Health (1936-1946), the Hispanic Foundation of the Library of the Congress in Washington (1941), the Pampulha Church, in Belo Horizonte (1943) and at the UN Headquarters building in New York (1952-1956). His portraiture, however, tends to remain denied during the analysis of his works.

The portraits done by Portinari usually depict common types of people (perhaps the closest to his widely publicized work), family, friends, and members of the society. Portrait of Paul Rossi Osir is one of the two existing paintings of his friend, who was also a painter, with whom Portinari regularly exchanged letters about their works, besides collaborating and culturally supporting Rossi Ossir. It is presented free from the constraints of academic scholarship, unlinked from an idealized and naturalized perception of the portrayed. The painting seems to bring much more than just the artist's anatomy, some inner way more intimate than directed to a specific type of persona in society.

Plastically, the fluidity between the figure and the background, limited almost by the color itself, and not dependent of the illusion of the traditional volumes and shading, makes it closer to Semeghini ( Portrait of Gianna , 1931), with which it shares some chromatic transparency, marked by a very thin and delicate linework, present as well in Soffici ( Procession II , 1933). On the other hand, the other potrait of Rossi Osir (Palácio da Boa Vista collection), as well as IEB's Portrait of Mario de Andrade , both from 1935, retain a less fluid emphasis, closer to Guignard's Self-portrait , 1931, with a background that shares some of Carrà's metaphysical language of synthetic elements.

Maria Lívia Góes

***

Scipione - Oceano Indiano,1930 >topo

This work differs within Mafai´s repertoire: the scene is hardly visualized as concrete. It is an oneiric, allegoric, metaphoric universe…mental space placed in painting.

Somehow, it also refers to the Northern European painting: with characters, with the objects arrangement, it drives us this time to collecting, to the wunderkammer [Cabinet of Curiosities] of the 17 th century, typical of the Flemish region, for example. It is the European eye, baffled and amazed, for the first time turned to the mysterious Orient; when it comes to the light, it deals with the 17 th century chiaroscuro , of Caravaggio, Gentilleschi or El Greco, studied by Scipione. The choice of the painting medium is also peculiar: wood instead of canvas, also evoking the past time textures and techniques, of the altar piece or even the less informal scenes of the S eiscentos .

But more than a simple tribute to the 17 th century, Scipione´s painting belongs to his time and to his author. Indian Ocean also deals with the recurring themes of his work, such as discomfort, guilt and regret (personal themes, which belong to the same 17 th century universe, up to a certain degree). Scipione's consciousness lies in the middle of the catholic guilt and sin, simply because of the human existence itself is present in this work, that morally condemns, for the simple fact of existing, any living form, and even in the greatest ends of nature. Therefore, this is the moment in which animale in gabbia [caged animal] is inserted theme that belongs to both the collecting of the 17 th century, amazed by the New World, and also to the grotesque imprisonment, half man – half animal, that couldn´t be free from guilt and original sin, even if he were out of civilization. After all, what is the threshold of Paradise and Hell, out of civilization?

Indian Ocean is a peculiar painting even in the scope of the artist´s repertoire, capable of communicating its discourse through melancholy and serenity almost paradoxical to the expressionist subject-matter that, even so, it does not let go of.

Benjamim Saviani

***

Gino Severini - Mulher e Arlequim,1946 >topo

.jpg)

The Commedia dell´Arte theme was frequently worked by Severini, by means of a variety of plastic solutions, being one of his favorite subject-matters. It is worth remembering that the artist wore harlequins and punchinello masks many times and also the painting standing in this rack when he passed away was precisely that of a harlequin. Léonce Rosenberg, who was his art dealer for about twenty years, used to stimulate him to focus on this kind of work, once the art market was favorable and also because the theme had become his “trade mark”. Two of his most important works depicting the theme were the frescoes to Montegufoni Castle made in 1921-1922 and the canvas to Maison Rosenberg in 1928-1929, both creations related to the “Return to Order” period.

In the case of Woman and Harlequin , it is clearly seen that just like in Flowers and Books and in Figure with Music Score from MAC USP, Severini embraced another grammar in comparison to the one from previous decades, making use of the language developed by the artistic avant-garde of the beginning of 20 th Century. Thus, the plastic solution used in Woman and Harlequin clearly refers to Henri Matisse´s production, once it incorporates a rich use of colors, the black as a color itself, thick outlines, decorative elements, such as tapestry, pillow, wallpaper, arabesques, typical of this repertoire. If during the 1910s Severini hadn´t been attracted by the French master poetics, the 1940s marked certainly a significant change, and his creations started referring considerably to Matisse´s oeuvre. This artistic orientation can also be found in his writings such as the monograph he dedicated to Matisse in 1944, in which he described the artist as a true “architect of sensitiveness”. The result accomplished in the French artist´s work was exactly what Severini was seeking for his own creations in those years. And from those works he was able to reach a painting of joy and compositional flexibility, which in Lionello Venturi´s view in 1961, was the summary of the glorious fantasy developed during the 1910s, after a less meaningful period in the art he produced during the interwar period.

Renata Dias Ferraretto Rocco

***

Gino Severini - Figura com Página de Música,c.1942 >topo

.jpg)

Gino Severini painted many female figures during his career, from cabaret dancers in the period he participated in the futurist movement, to ballerinas depicted in an abstract way at the end of his life. These two moments in his artistic career could also be seen in the works that the artist exhibited in the second and fourth editions of São Paulo Biennial.

When it comes to Figure with Music Score, it is clear that just like in the other female compositons developed throughout the 1940s, Severini referred to Henri Matisse's poetics, above all to his “Nice Period”, both regarding the subject and the plastic solution applied. In this canvas, in which there is a female figure, most probably the artist´s wife, Jeanne Fort Severini, whose arms are resting on a music score, inside a household space, Severini worked with thick outlines, arabesque wallpapers in the background and a well-ornamented curtain. All elements are framed in a closed scene, in a highly decorated environment, which the main focus is precisely the female figure, who looks quiet and thoughtful. Her dress is worthy of special attention, because it seems to be a misplaced element, once it does not have a correspondence when it comes to the outfit worn in the period in which the work was painted. But it is a fact that the outfit brought about such a plastic effect that Severini dedicated himself to the choice of the dresses worn by the models who posed for him, and that also was something that drew his attention regarding the creations of other artists, which is confirmed by a comment he wrote on a reproduction of La Danse à la Ville by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, in which he highlighted the beauty of the dress depicted. As for the colors used, one can notice here that Severini worked with warm colors in the main figure, but in a lighter way and less vibrant and not so pure in comparison to Matisse´s creations.

It is still important to point out that besides the reference to the French master, there is a correspondence with part of the Italian production of the same years, which constantly depicted female figures in the household environment, verified in the scope of painting and also in productions of a different nature, like the printing of periodicals addressed to women and household, such as Rivista Bellezza and Stile, among others. Severini's interest in the press at that moment was significant, which can be proved by the comments he made in 1940 on the magazine covers and drawings by Achille Funi and Giorgio De Chirico to editions of Rivista Civiltà and Aria d´Italia .

Renata Dias Ferraretto Rocco

***

Gino Severini - Flores e Livros,c.1942 >topo

.jpg)

The plastic solution applied in Flowers and Books was widely used by Severini at the beginning of 1940s, as one can see in his works exhibited at the IV Quadriennale di Roma in 1943 and many other exhibitions in Italy in that decade. Upon observing the painting, it is clear that the artist worked with a language close to that one of the artistic avant-garde of the beginning of the 20 th Century, which in this specific case, would be like resuming the cubist poetics, which the artist had experimented in the second half of the 1910s right after his participation in the futurist movement. During the two decades that preceded the development of Flowers and Books , Severini had been working based on other orientations, essentially in relation to the so-called “Return to Order” spirit and from 1940s on, he again valued the avant-garde experiments. This recover y is evident in a letter he addressed to the artist Renato Birolli in 1942, when the discourse was about the greatness of Picasso´s art, affirming that this artist was capable of establishing new conditions in art, whose invariables could be equally found in Caravaggio´s or Piero della Francesca´s legacies. Therefore, even if Severini was still living in Italy then, he started to embrace as a model, no more the artistic language developed by the masters of the Trecento to Cinquecento as he had done during the interwar period, but that which he had witnessed and experimented in the 1910s in France .

In this sense, it is interesting to observe both his still lifes that belong to MAC USP together, once they are the precise reflection of Severini´s artistic career change during the 1930s and 1940s. In Flowers and Books, it is possible to see a less rigid composition, developed based on more colorful and lighter brushstrokes that suggest movement and fluidity. There are shadows designed in a cubist manner, in contrast to a very decorative background. There is no metaphysical aspect or what the artist called “transcendental realism” (in reference to the creations in 1920s and 1930s), once in this work he dealt with the instant present, finding again – in his own words – life and expression.

Renata Dias Ferraretto Rocco

***

Gino Severini - Naturexa-morta com Pomba,c.1938 >topo

.jpg)

In 1935, at II Quadriennale di Roma, Severini was granted with the highly sought-after 1 st - place prize for his painting exhibited in his personal room where he presented thirty six works. Due to this reward it became possible for the artist, who had been living in France for many years, to return to Italy in a great style. Among the twelve still lifes exhibited then, there were at least two whose plastic solutions were very similar to the one used in Still Life with Doves . They all show a rigid composition, static and solemn. The depicted objects, taken from the artist´s private collection, are properly positioned to suggest harmonic structure based on geometrical relations, which is comprehensible if we consider that in the 1920s and 1930s, Severini believed that art could only be universal if it had been based on numeral laws. A metaphysical note can be noticed in these works, in which the elements are surrounded by nothing, and the tray on which the objects lie seems to be floating, suggesting a sense of non-spatiality. The color palette was reduced, and its use was completely controlled, for what mattered to the artist, above all, was the strength of the drawing. Thus, there is no trace of the abundance and the color vibration of his futurist works, which only would be revisited by him from 1940s on. The presence of doves and grapes here also deals with an important aspect, once it evokes religious issue, something essential to the artist and that was also a prevailing issue during the interwar period. In this sense, the ascent of a character such as the neothomist French philosopher Jacques Maritain, Severini´s close friend, proves that.

It is interesting to ponder over the still life gender in the general context of Severini´s production, because if Still Life with Doves and similar works developed in the 1930s can be understood as representative of his vast production with this subject in consonance with the artistic spirit of the “Return to Order” environment, in the following decades, they embraced another appearance, for there is again an approximation with the artistic avant-garde of the beginning of the 20th Century. In the case of his creations at the beginning of the 1940s, his relation to cubism is clearly noticed, and at the end of this decade to abstractionism. As Lionello Venturi pointed out in the monograph that he dedicated to Severini in 1961, from his still life, it is possible to see clearly the gradual change in the artist´s style along the decades.

Renata Dias Ferraretto Rocco

***

Paulo Rossi Osir - Velha Ponte,1927 >topo

The classical and erudite training of Rossi Osir, often praised by critics like Sergio Milliet and Mário de Andrade, is connected to his studies in Europe, especailly at Brera Academy, in Milan, where he graduated in architecture.

In 1920, he brought to Brazil the Italian Art Exhibition , by which he started to work as a cultural representative of some sort, responsible for group exhibitions, such as the Salão Paulista de Belas Artes [São Paulo Salon of Fine Arts] (1934), in addition to the artistic promotion of the Sociedade Pró-Arte Moderna (SPAM) [Pro-Modern Art Society], the Família Artística Paulista (FAP) [Paulista Artistic Family] and the Santa Helena Group, until his peak with Osirarte, the artistic tile studio where not only he elaborated tiles for Lucio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, Cândido Portinari and Burle Marx, but also hired artists Alfredo Volpi and Mário Zanini. The “Return to Order”, in its varying degrees is present not only in his production, but in those in which Rossi Osir, as a cultural representative, promotes. His artistic production is closely related to the Italian Novecento.

The modern language appears in his work through the lessons of Cézanne, and it is mainly present within his landscapes, which were essential to his studies with Donato Frisia in 1924. As a result of this new approach to painting, this time using oil, and not watercolor, and with an investigative nature, we can find the work Old Bridge , from 1927. In it, we are able to perceive the prevalence of the landscape/vegetation, which occupies almost the entire scene, outlined by the brushstrokes and the colors transposed to the support. Without the presence of preliminary drawing or the construction of a perspective; rather the landscape seems to be revealing itself during the direct act of painting. Even the skyline set by the bridge integrates the whole set, not being part of a pre-conception, alas, from an apprehension of the whole.

The painting was acquired from Rossi Osir's widow, Alice Rossi, during the VII Bienal de São Paulo (1963), when the newly founded MAC USP began to create its own collection. At the time, it was presented hors-concours under the title Olivais, Cervo Lígure [Olive Trees, Cervo Ligure]. This title, which reveals an inscription on the bottom right corner of the painting, under the painter's signature, however, would indicate the place where the work was made, performed in the painter's last period in Europe (1924-1927). In its first presentation, during the IIIª Exposição do Pintor Paul C. Rossi em São Paulo (1927), the painter named it Old Bridge .

The original title approaches this painting technically and thematically to Arturo's Tosi's Zoagli's Bridge . Rossi Osir shares with Tosi what would be the most typical aspect of the Novecento: the classical language of the Renaissance as a stylistic reference, but mostly, although this cannot be identified within the Italian movement, both are followers of Cézanne. The derivative term of the French painter is perhaps most explicit in Osir's bridge, where nature seems to take over the whole composition, almost as if it had a life on its own, while in Tosi's, it's still somehow limited by the drawing's contours. Other landscapes painted by the Italian, especially those of Val Seriana, however, achieve Cézanne's lessons closer to Rossi Osir's. These are the cases of Val Seriana and Landscape , 1946.

Maria Lívia Góes

***

Mário Zanini - Canindé,c.1940 >topo

The painter, originally from the working class, has educated himself during art classes at the Liceu de Artes e Ofícios (São Paulo Academy of Arts and Crafts), and although he had dedicated himself to easel painting since 1923, only during the 1930s he could finally share a room with Rebolo, which became his studio, at the Santa Helena Building. In the same decade, he participated in his first collective exhibition, São Paulo Fine Arts Salon, in 1934. He did his first solo exhibition in 1944, at Brasiliense Bookshop, but he wasn't the kind of artist that used to promote himself.

His plastic expression is a reflex of his trajectory, concerning both to the subject-matters chosen and the language adopted. As his comrades from the Santa Helena Group, Zanini didn't abandon figuration, even when he made his incursions to abstractionism, and the motives he explored were the same that surrounded him: floodplains, riparian zones, an iconography of the humble and their spaces, transposed deeply into the canvas.

The language that will express that reality modifies itself according to the painter's studies. With a technical education but with no direct contact with artistic avant-garde, Zanini lined himself up with the “well-behaved” modernism of the interwar period. Therefore, if his paintings show impressionist and expressionist features, it is not derived from a direct affiliation to these Schools. His artistic language resembles that of Corrente , group of Italian artists opposed to the conformism of the Novecento , the fascist regime and the formal problems of abstraction, united through expressionism. That expressionism was initially lyrical, but became more and more realistic, defined by color, light and expression of dramas and passions of the existence.

With them, he shares the feature of a great colorist, which we can notice at Canindé , such as the gestural brushstrokes, expressionist traits used by the painter. He portrays, with affection, a daily scene of the surroundings of Tietê (an everyday that he also shares) and constructs a perspective which startpoint is the painting itself, which is created through the brushstrokes and the color, without losing its contours.

Maria Lívia Góes

© 2013 Museu de Arte Contemporânea da Universidade de São Paulo